“Instead of working to break down the walls of segregation and the poverty trap they had created, the ghetto would be sent entrepreneurs.”

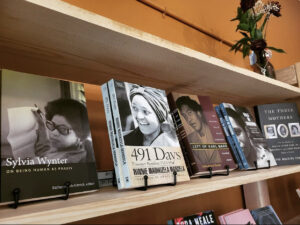

Mehrsa Baradaran, The Color of Money: Black Banks and the Racial Wealth Gap

Mehrsa Baradaran’s The Color of Money is a game-changer. While I’m already a sucker for intricate research and well-reasoned analyses, Baradaran traces the history of the racial wealth gap in a way that completely reimagines Black economic empowerment. Check out my top three lessons from The Color of Money below!

1. The same forces that create the need for Black banks also prevent their success.

In 1863, Black people owned 0.5% of the nation’s wealth. Over 150 years later, Black people still own less than 2% of total wealth in America. Both then and now, communities turned to Black banks to advance wealth generation–relying on Black banks to alleviate poverty caused by housing segregation and racism. However, even as institutions responsible for economic development, Black banks have also been victims of the same poverty and discrimination that plague the communities they serve. Ultimately, Black banks are forced to do more with less, resulting in Black capital being drained into mainstream banks. And, in times of crises, Black banks are less likely to receive bailouts or access to safeguards that prevent bank failure.

2. Black capitalism is STILL capitalism.

Though Black Americans have experienced some accumulation of wealth, those gains are largely concentrated within the middle class, and they rarely trickle down. Early Black activists called for economic self-determination, and eventually policymakers coopted those efforts into Black participation in free-market capitalism–the very system that created the racial wealth gap in the first place.

3. Government intervention is a double-edged sword.

Spoiler alert: State-sanctioned discrimination and segregation are responsible for the racial wealth gap. But who is supposed to fix it? On one hand, policymakers emphasize Black entrepreneurship as a mechanism for economic reform, directing efforts toward initiatives such as “enterprise zones” and “community capitalism.” Others argue that these initiatives are political decoys that enable the government to avoid fundamental reform, and they undermine demands for economic redress and reparations. Existing policies provide little support, and they put the onus on Black entrepreneurs to unilaterally fix the poverty problem–a problem created and perpetuated by the government.

Grab a copy of The Color of Money from your local Black-owned bookstore, and let me know what you think!